Summer Is Icumen In

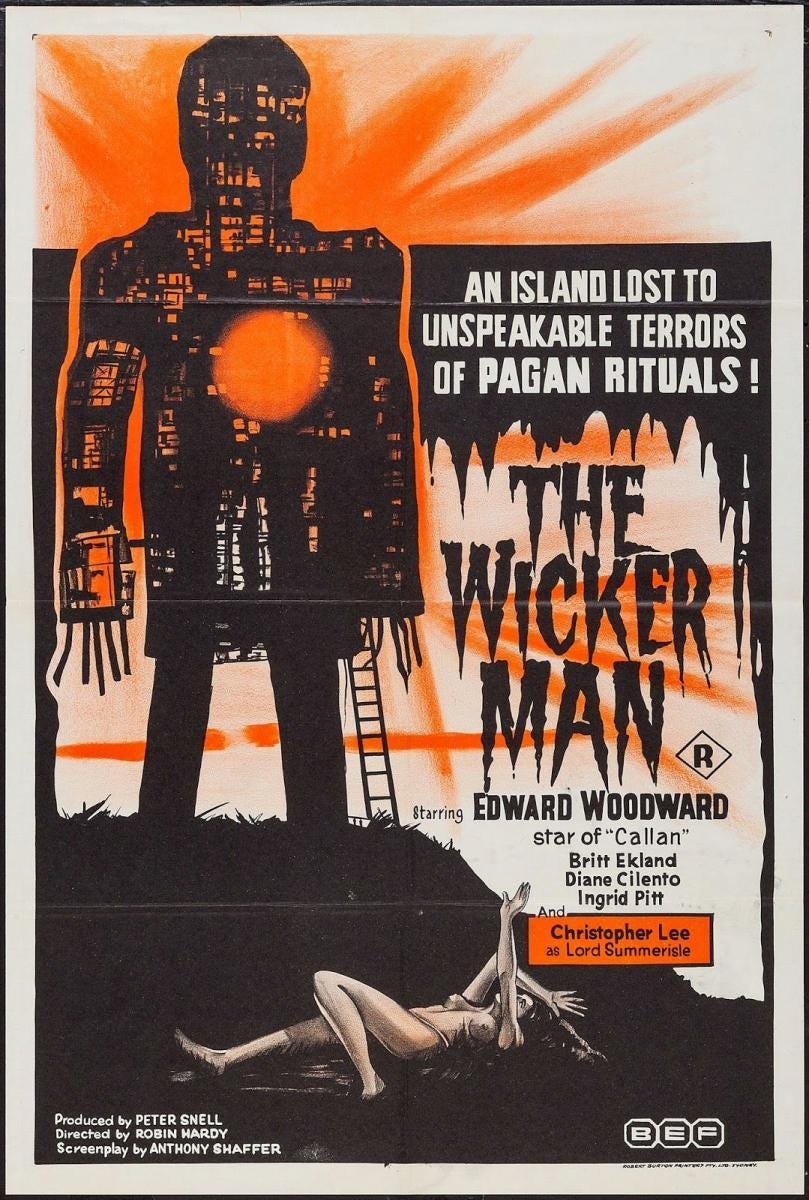

I've been trying to remember when I first saw The Wicker Man, which celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. I want to say that I watched it as the first presentation in BBC2's Moviedrome strand, when I was seventeen. I remember Alex Cox's introduction, particularly his claim that the original print of the film, containing many crucial scenes cut from the theatrical release, ended up being buried in the pylons supporting the M4 motorway, a possibly true urban myth that added to The Wicker Man's cult allure as a film that was somehow both lost and about to be shown on mainstream TV.

The only problem is that my diary for that date, May 8, 1988, makes no mention of me seeing the film, and in fact tells me that on that evening I saw goth-rock band Fields Of The Nephilim live for the first and, it turned out, the only time (it was a brilliant gig). Moviedrome started at 11pm, so it's possible, if unlikely, that I made it back from the concert in time to watch The Wicker Man and, in my excitement over the Neph, forgot to mention it in my diary. I'd like to believe that's what happened. Fields Of The Nephilim followed by The Wicker Man: what a fantastic, formative night for a 17-year-old goth that was.

More likely though is that I saw it a few months or even years later, on a taped-from-the-telly VHS at a friend's house. We didn't have a video recorder till the end of 1989, and I'm pretty sure none of my schoolmates were into The Wicker Man, or Moviedrome-type cult films generally. But I had cooler friends than those I went to school with, and my pal Fenkins always had a stash of tapes that he took to house parties, for the hardcore to watch after things wound down and dawn slowly seeped through someone's parents' net curtains. The Rutles was a big favourite, I remember. But The Wicker Man? I can't quite place it in that context.

The other candidate for folk horror conduit would be my friend Helen. Visits to her in Rochdale and then Manchester generally involved all-night movie marathons drawn from the huge library of cult films she (and later her housemates) had accumulated. Maybe I saw The Wicker Man first with her, perhaps a tape of that same Moviedrome screening complete with intro. Or maybe I'm conflating the Alex Cox introductions to the many Moviedrome presentations I definitely did see with reading the motorway landfill story in the NME or somewhere.

Certainly, The Wicker Man feels like a film I've always known, one that's always been a part of me. Remembering that it wasn't readily available or that well-known in the eighties and nineties, and that it was over ten years before it was shown on UK TV again, is strange given its present ubiquity and firm status as a classic British film. Recently I rewatched it in the 2001 Director's Cut, on one of the first DVDs I ever bought, soon after it came out.

As with all great films, The Wicker Man changes over time, and you see different aspects to it every time you watch it, your perspective changing as you get older and the world you live in becomes a different place. If you're the kind of person who is drawn to The Wicker Man then you probably feel like a bit of an outsider, someone out of step with mainstream culture. As such, you probably sympathise with the pagans, even though you know they're a murderous lot, complicit in their own manipulation by Christopher Lee's ruthless and conniving Lord Summerisle, and even though the death of Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) remains shocking and tragic despite the years of parody and camp recontextualization.

That sympathy is perhaps deepened for anyone who was a child in the 1970s or earlier, especially if you grew up in a village or small town. For me, just a couple of years older than the film itself, there's so much in there that reminds me of my own lost childhood. Watching The Wicker Man in 2023, Summerisle seems like an idyllic place to live. It's easy to imagine that, in some way, I once did live there. I can remember when all of my friends looked like the boys and girls in the village school. I remember dancing round a maypole to unctuously performed folk songs, unstructured lessons full of local history and legends, and class trips to the nearby graveyard to take brass rubbings. I never actually put a frog in my mouth to cure a sore throat, but there were plenty of other "traditional" remedies for common ailments that were earnestly insisted upon by someone's gran or weird auntie. And as if growing up in rural Yorkshire wasn't folk horror enough, I later learnt that our annual family holidays throughout the seventies and early eighties, which were always taken in the vicinity of Kirkcudbright and Gatehouse Of Fleet in Galloway, were close to where The Wicker Man was filmed.

Of course, like all supposed golden ages, this version of my childhood is a myth. Growing up in the seventies wasn't really idyllic, any more than Summerisle is really a pagan paradise. The crops are failing, requiring ever more extreme sacrifices, barbarity and wilful self-deception that won't help and just distract from the real problems. The old ways only go back to Victorian times, when an earlier Lord Summerisle cynically invented them in order to bind the island's population to his will (a nice acknowledgement of how most "traditional" folk customs that we're aware of now were similarly "revived" with a great deal of creative license in the Victorian era, though generally with less sinister intent).

It's tempting to think that once we lived on Summerisle, but that now the world is full of dreadful, pompous Sergeant Howies, poking their noses in, telling us we mustn't do things that we've been happily doing for generations, and threatening to report us to some bureaucratic centralized authority. But in fact, a more appropriate metaphor to draw from The Wicker Man in 2023 is that we're all living on Summerisle right now. The island is a prophecy of Brexit Britain, ruled over by high-handed autocrats who use the emotive power of invented myth to keep us working for their interests rather than our own, and to distract us from the fact that their crackpot schemes are tanking the economy and alienating us from our neighbouring nations. Ultimately, they whip up a frenzied hatred of outsiders, making them both scapegoats and sacrifice, as though if we could just shut all of the immigrants and woke police in a giant wicker man and burn the lot then everything would be alright.

But that won't restore the bounteous harvests of yesteryear and it won't bring back the golden past that never existed either. And even if it did, could it ever be worth it? The Wicker Man is a wonderful film that can be enjoyed on many levels. But if we want to find a reading that's relevant to our present moment, then I think the lesson should be don't get fooled again. Be a heathen by all means: but not, I hope, an unenlightened one.

In a final note, what with it being the film's fiftieth anniversary, I've seen a lot of discussion of the various songs and records that have been inspired by The Wicker Man over the years. But one that seems to always be overlooked or forgotten is also one of the earliest musical tributes to the movie, and a cracking song to boot.

The Mock Turtles may be remembered as baggy also-rans who licensed one of their more throwaway songs to a Vodafone advert, but before that they were a soaring, semi-psychedelic indie-rock group whose anthemic songs borrowed from The Byrds, Bowie, and Be-Bop Deluxe. In 1989, this Manchester band released an EP called Wicker Man on the excellent Imaginary Records label (Of Heywood, Lancs, and also home to the mighty Cud). The title track also closed the following year's Turtle Soup album.

Ramming home the source of their inspiration, the EP sleeve featured a striking still from the movie and the record also included a faithful reading of 'Willow's Song', maybe the first modern version of the film's most famous ersatz folk song, one that's been much covered since. But I think I'm right in saying that The Mock Turtles got there first.

I hope you enjoy the music and my ramblings. See you next time.

Ben

Super piece Ben. I think I also saw it first that same evening. My Dad (a scientist type with no interest in the arts at all) used to love Moviedrome, and we’d often watch it together so I must have seen it with him. Thanks

Lovely piece, Ben, thanks.